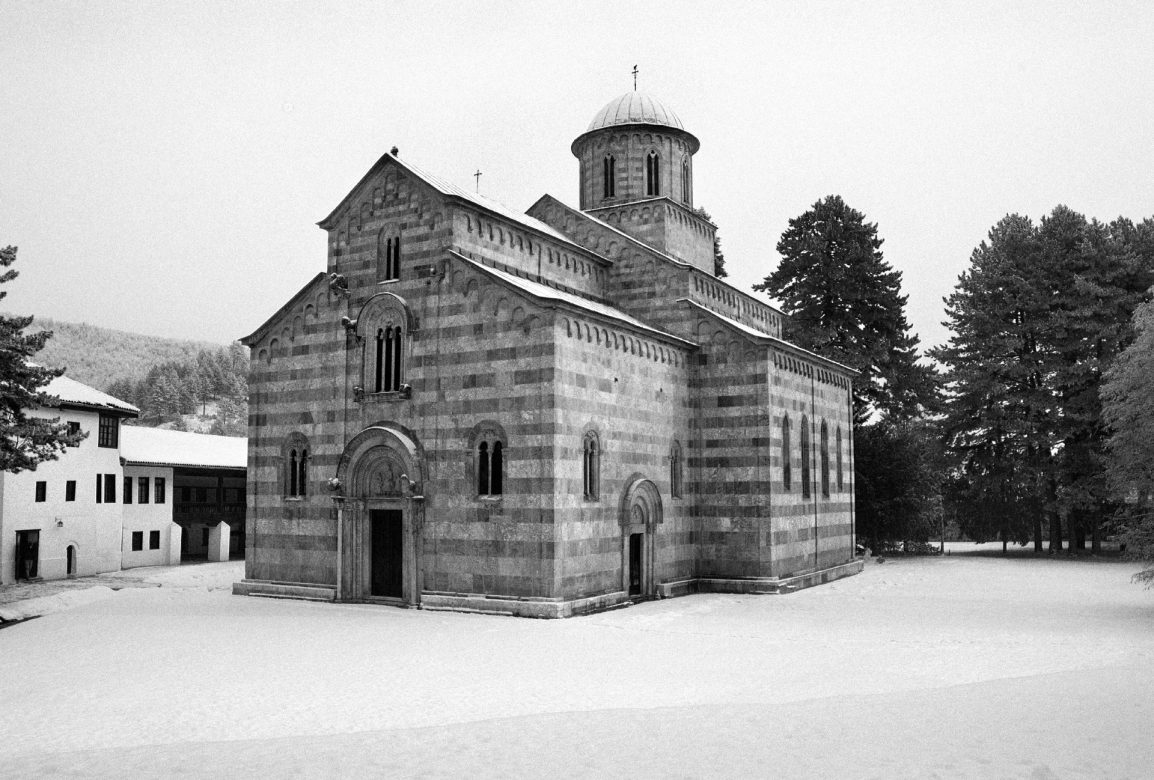

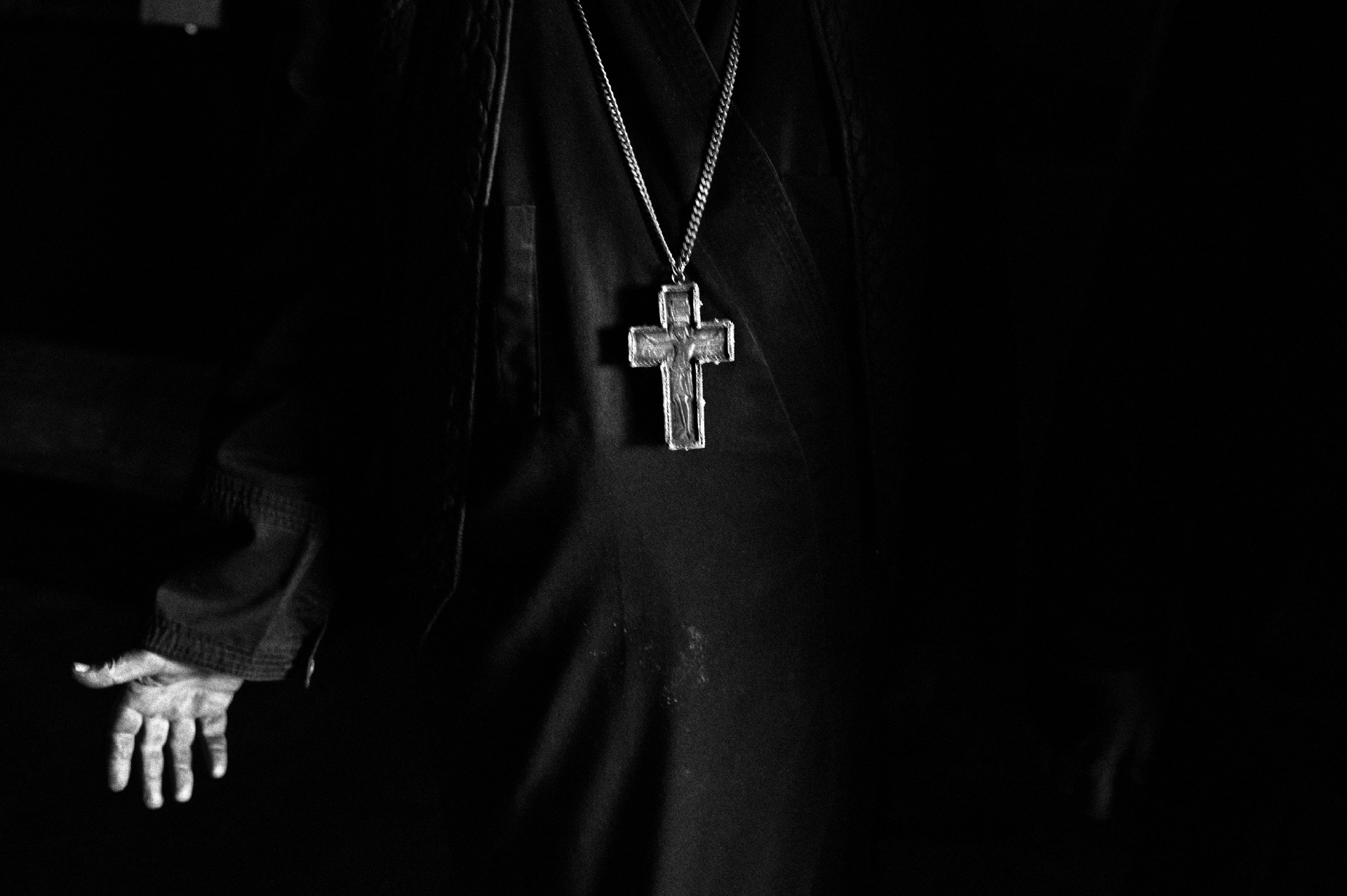

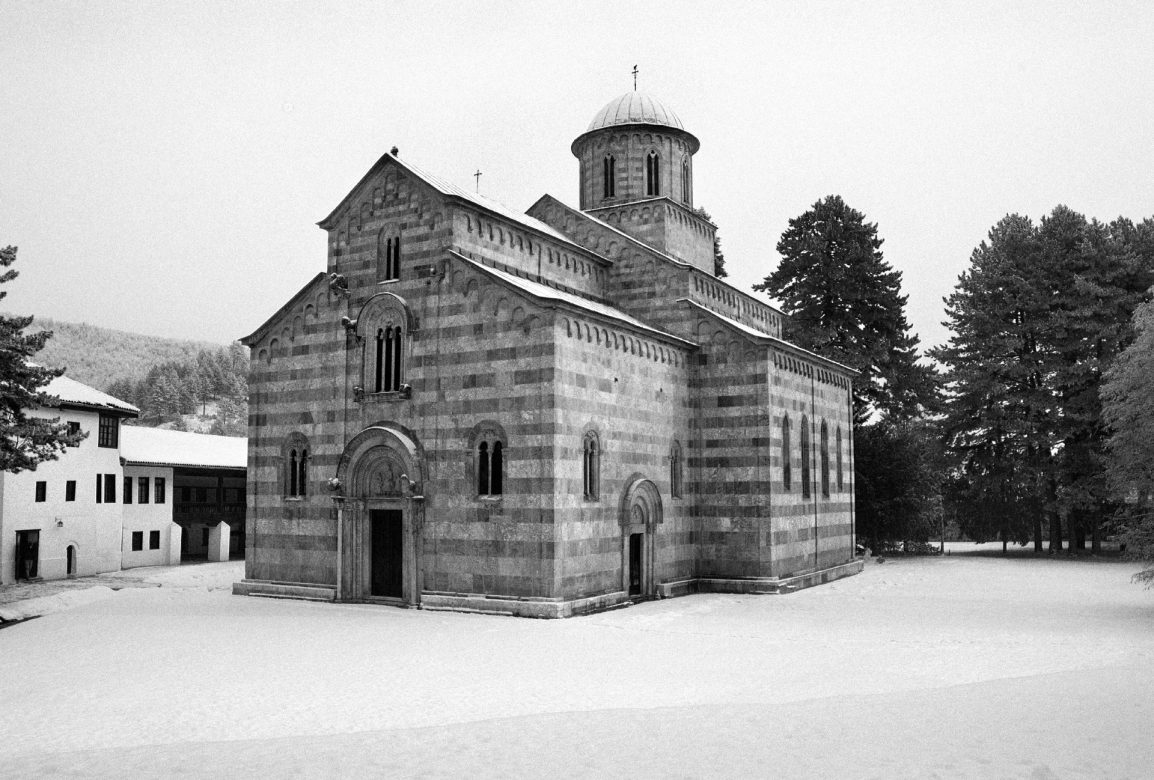

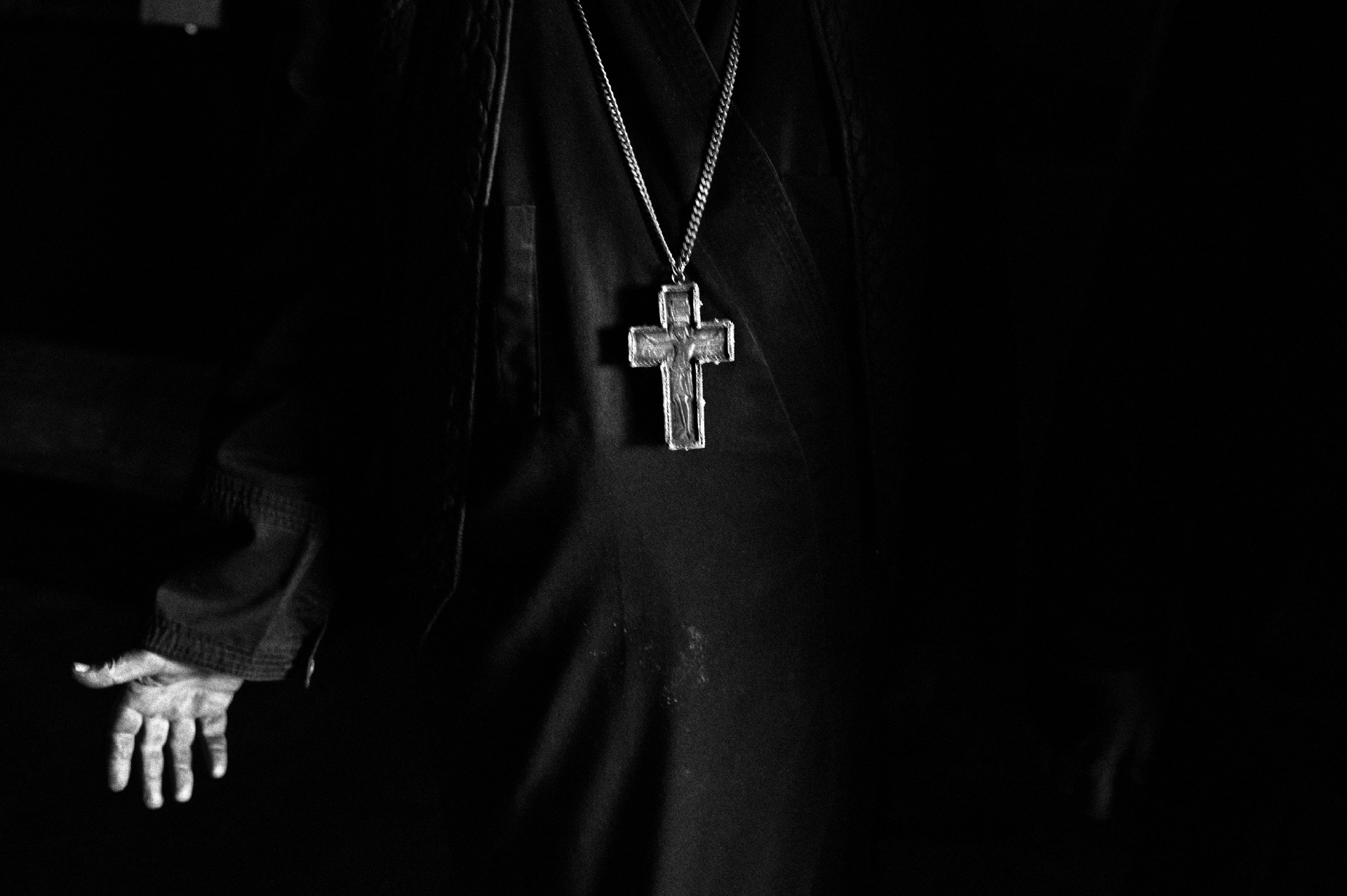

Visoki Dečani Monastery, built in mid-14th century, declared by UNESCO a World Heritage Site. It has been in full renewal for years: 35 monks live here, many of whom entered during the last 12 years. Dečani, 2011. Kosovo.

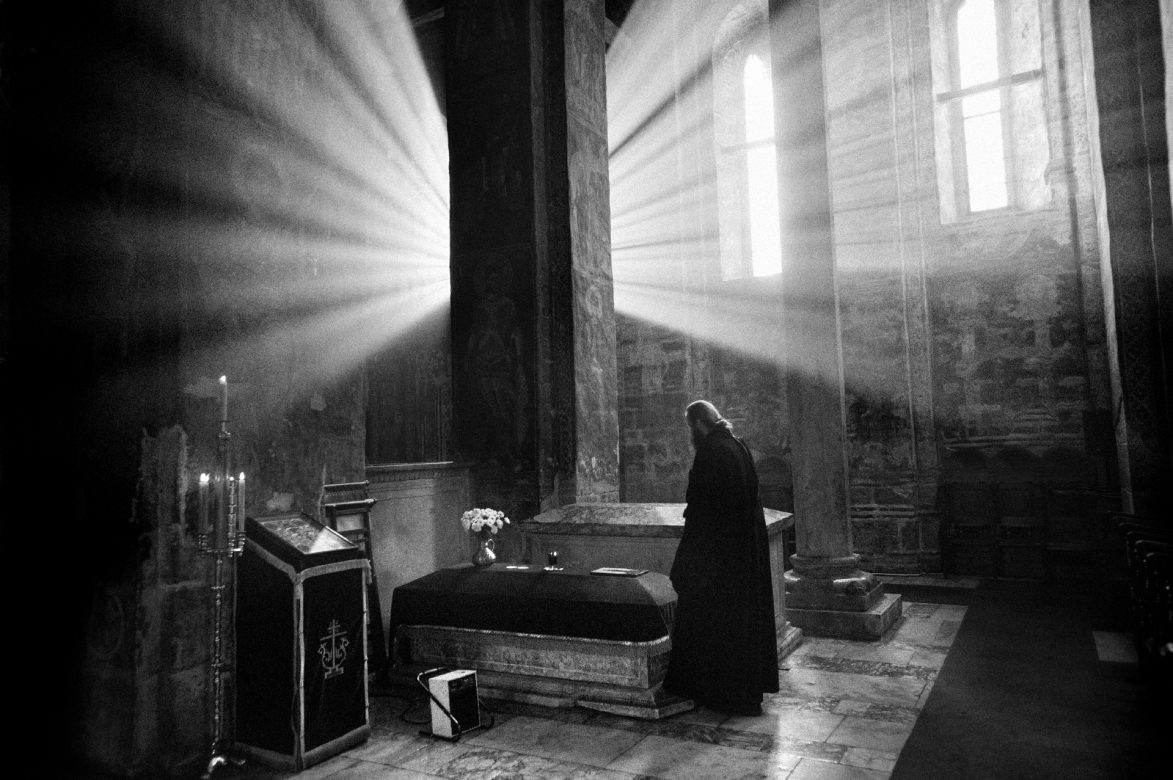

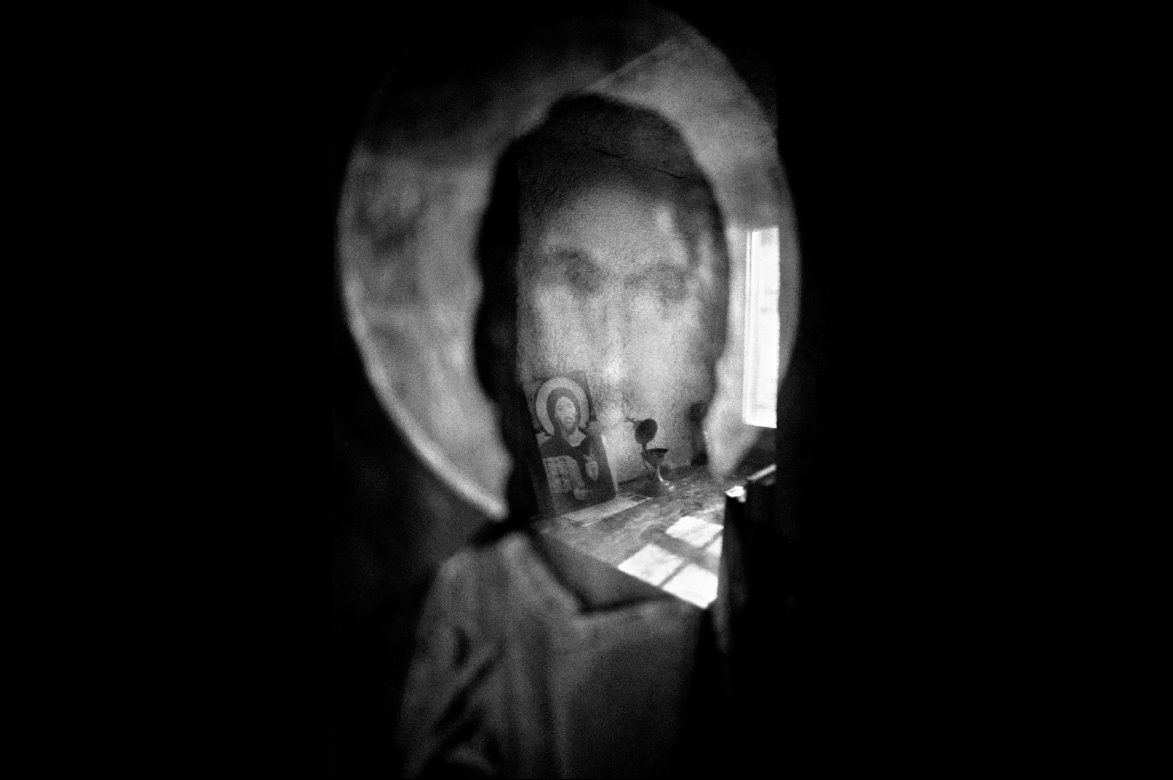

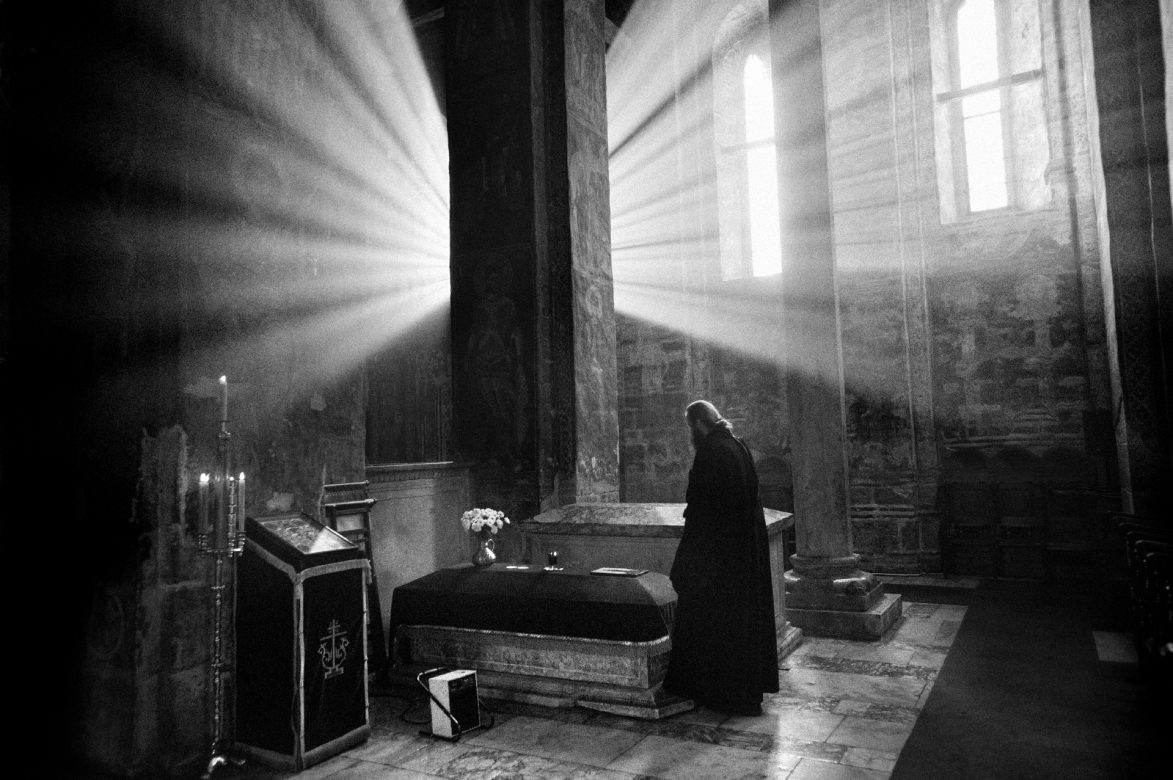

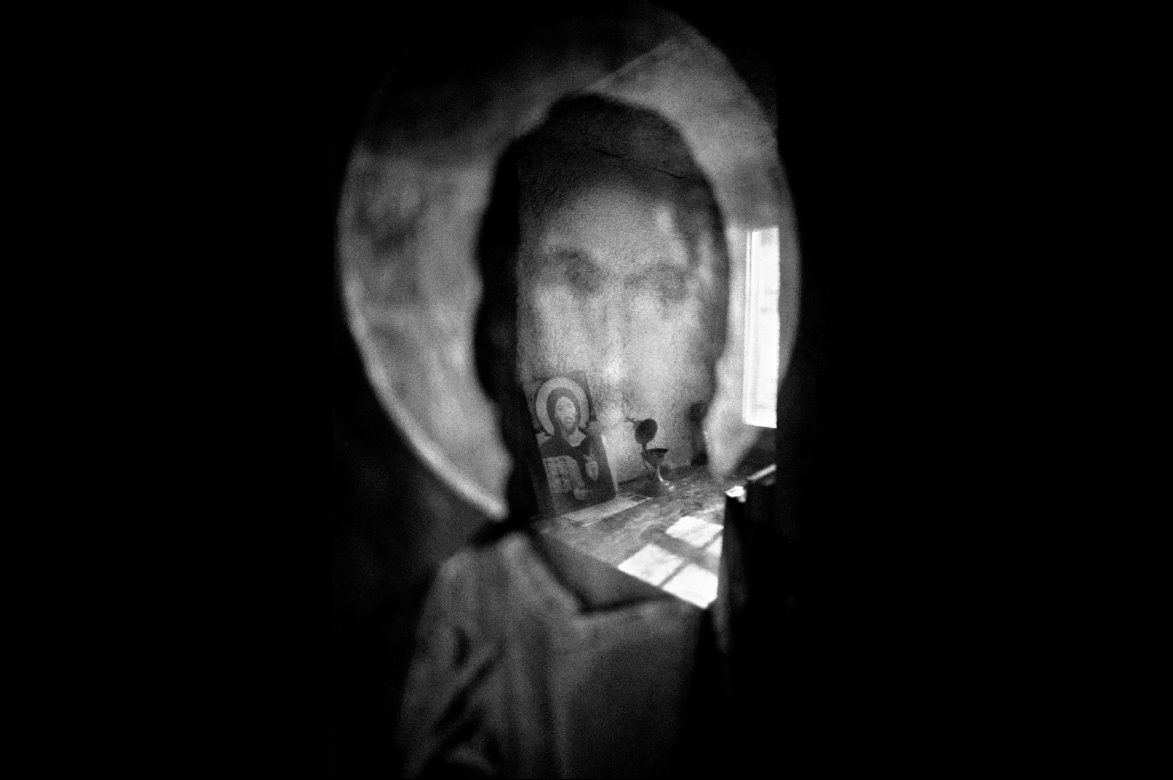

The Icon of St. Sergius Radonjeski, Russian Saint from the 14th century, kept in the church of St. Nicholas in the Patriarchate of Peć. The complex of churches is the spiritual seat of the Orthodox archbishops and patriarchs. From 13 July 2006, it was declared UNESCO World Heritage Site and is put on the list of World Heritage in Danger. Moreover, the facts of the pogroms of 2004 - assaults concentrated in a single day against several Orthodox monasteries - is under the protection of NATO with the Slovenian army. Peć, 2012. Kosovo.

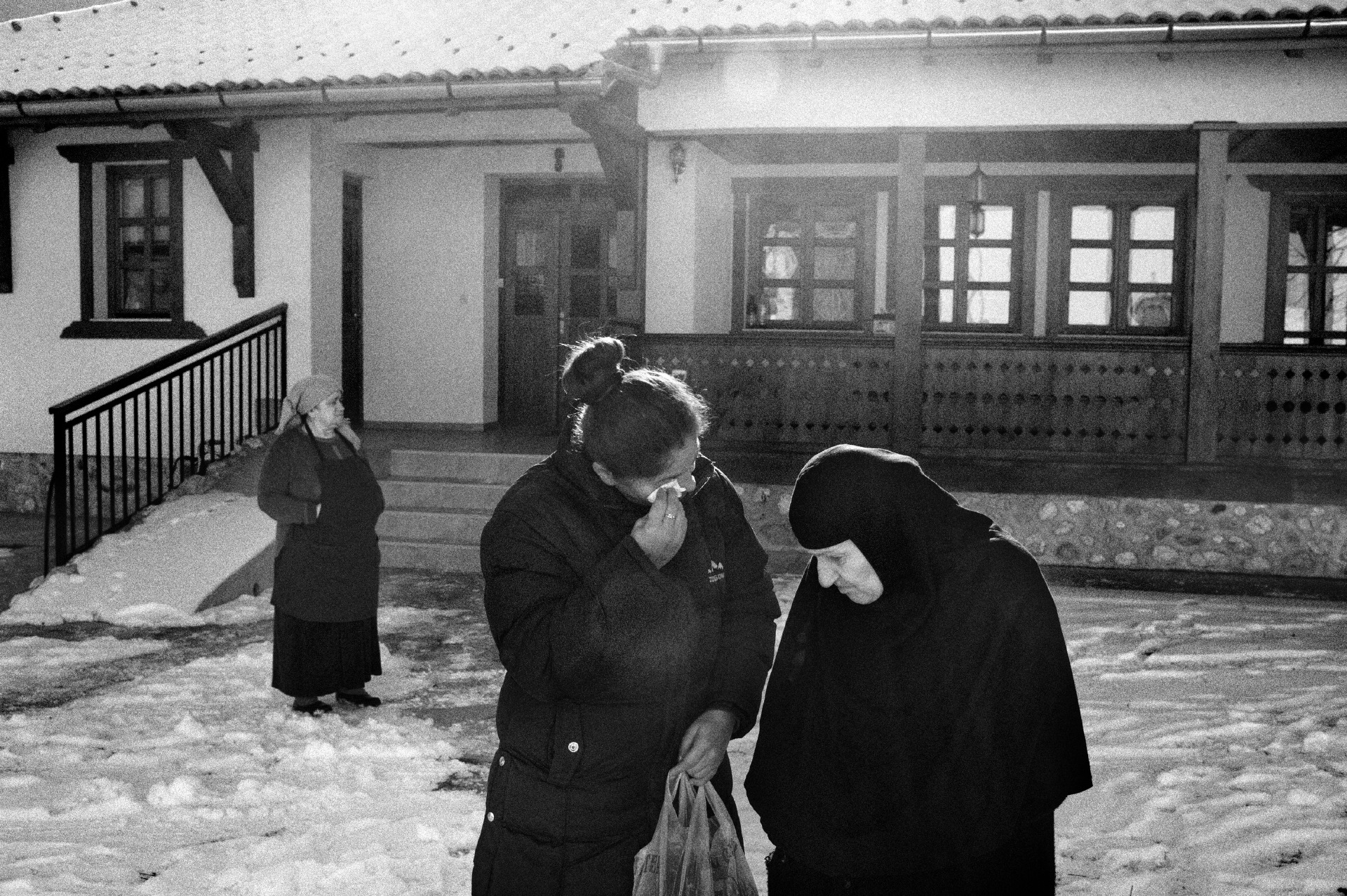

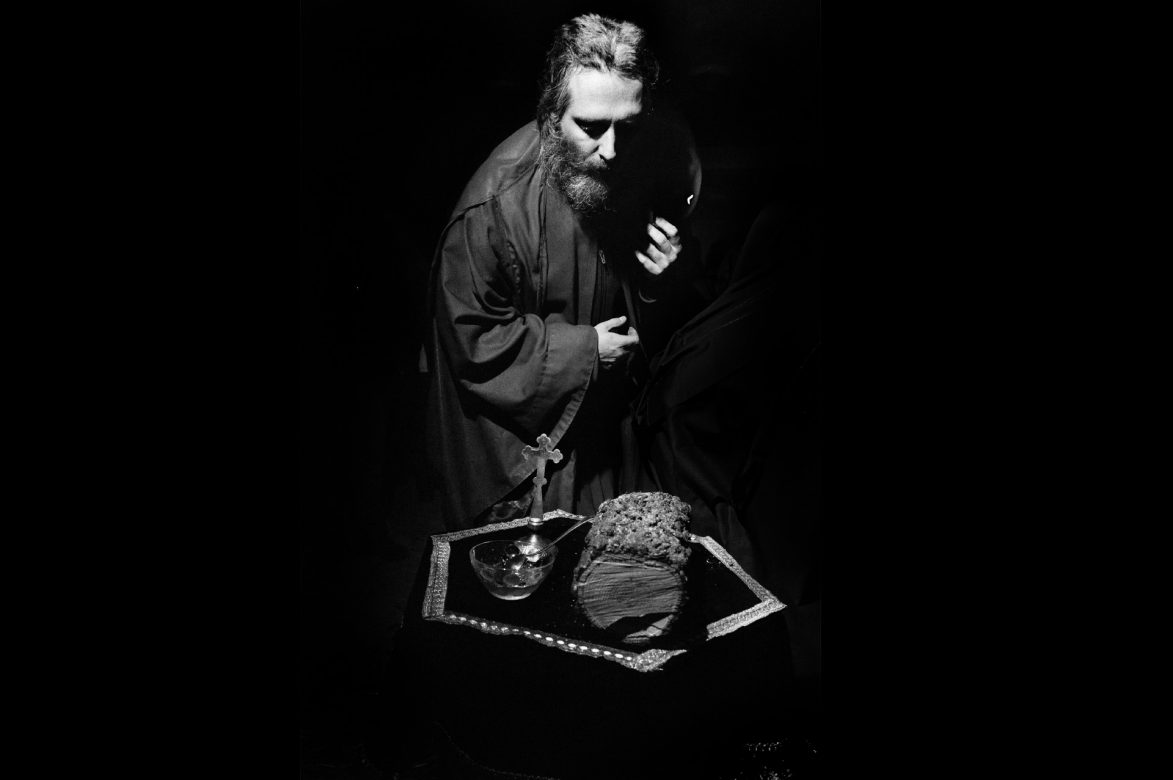

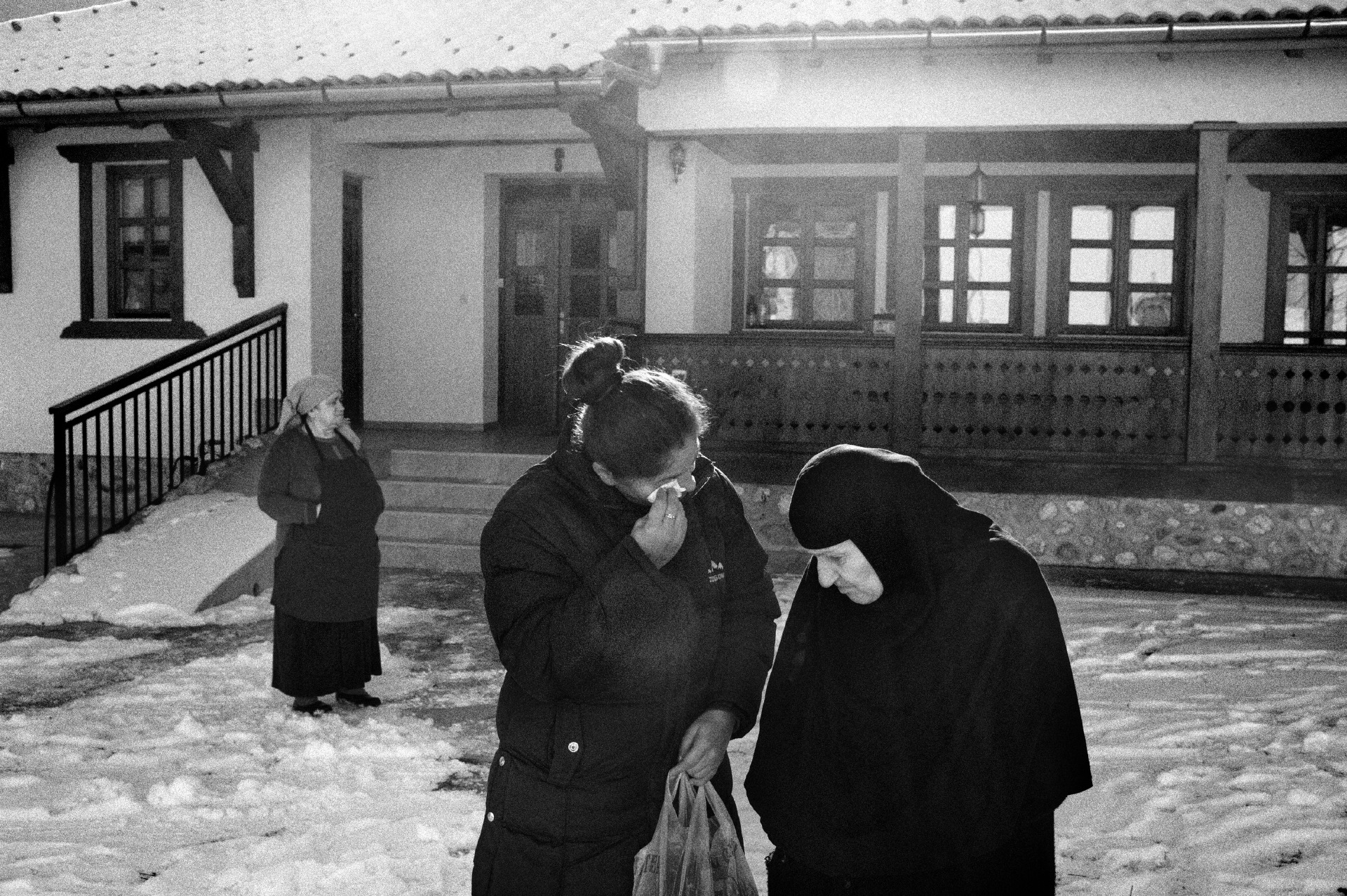

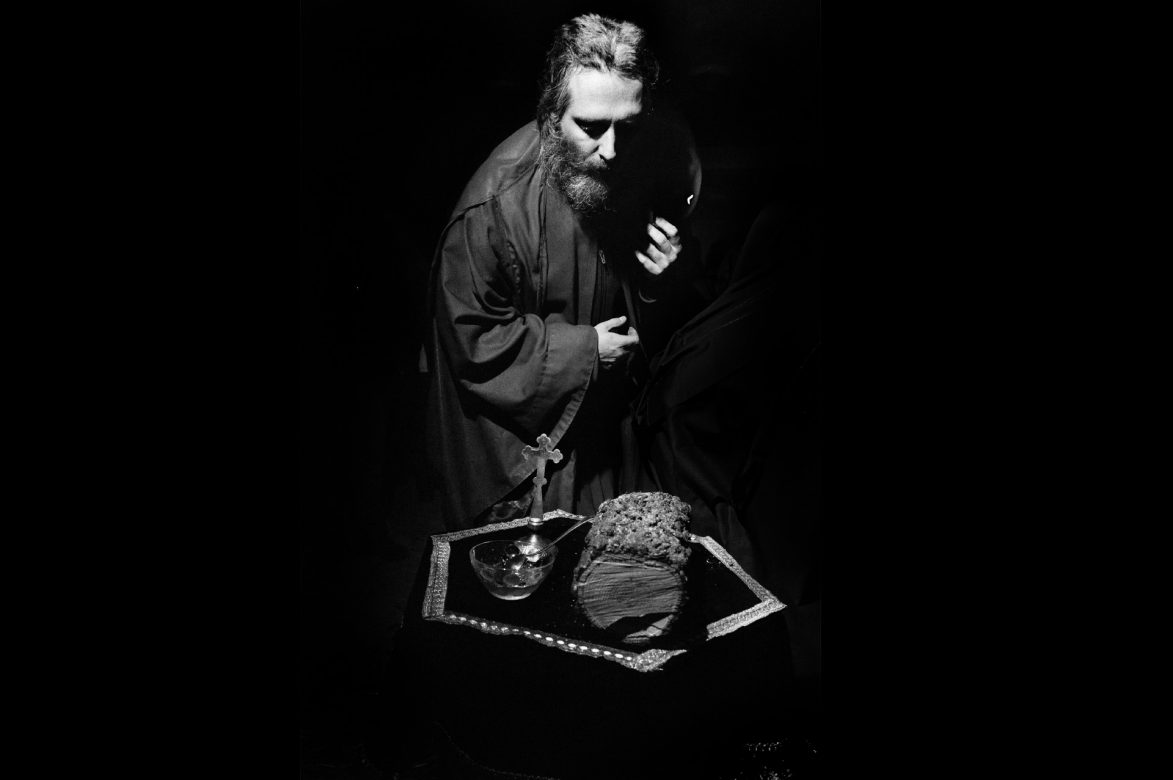

Faithful during the Christmas ceremony in the Visoki Decani monastery . The rite of Christmas is one of the outstanding dates of the liturgical year, during which the monasteries are filled with worshipers. Decani, 2012. Kosovo.

The road leading to the monastery of Decani is controlled by the army and partly closed by large concrete blocks. Dečani, 2012. Kosovo.

Looking for firewood in the mountains surrounding the town of Decani, a stronghold of the former commander of the KLA (Kosovo Liberation Army) Ramush Haradinaj. This area - after the bloody two-year period of '98-'99 - was the scene of an action of ethnic cleansing towards the Serbs, forcing them to emigrate. Decani, 2012. Kosovo.

Orthodox monasteries in Kosovo are exposed by extremist Albanians, to pressures and constant threats. Albanians still perceive the presence of the Serb minority as a remnant of the previous oppression and Orthodox monasteries are seen as symbols which need to be eradicated. So the monks can not live independently: to be able to go outside the walls monastery they have need an armed escort. Decani, 2013. Kosovo.

The marks left by the 1998-1999 war in Kosovo are still visible. The monastery of Zociste completely destroyed in 99 and rebuilt, in part, in 2006 thanks to the Italian army. Since the war ended more than 150 monasteries were destroyed. Those remaining, and the monks who live there, are under protection of KFOR. Zociste Monastery, 2013. Kosovo.

The "Plain of Blackbirds". June 28th marks the commemoration of a very important historic battle for the Serbs, the Battle of Kosovo Polie. This battle was fought on June 15th, 1389 (the day of San Vito) by the Serbian army against the Ottoman army in the "Plain of Blackbirds". The battle is considered by Serbs as one of the most important events of their history and is a source of great part of their national feeling. Kosovo Polje 2012. Kosovo.

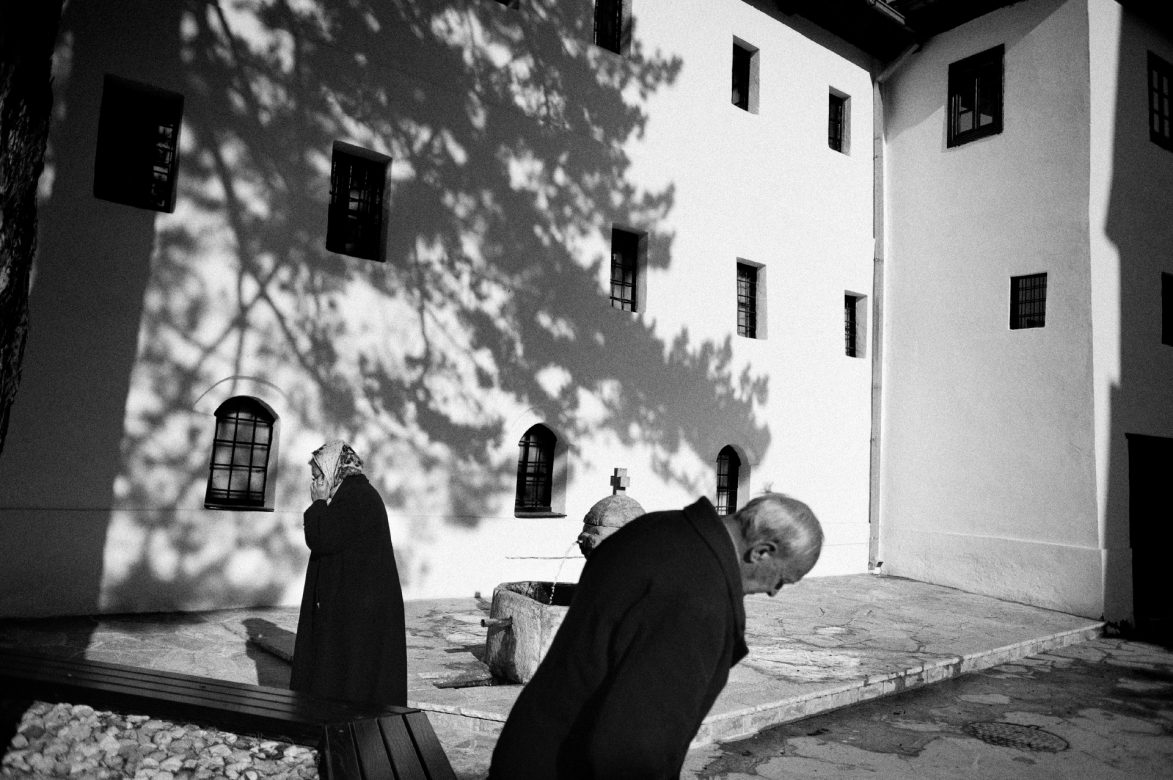

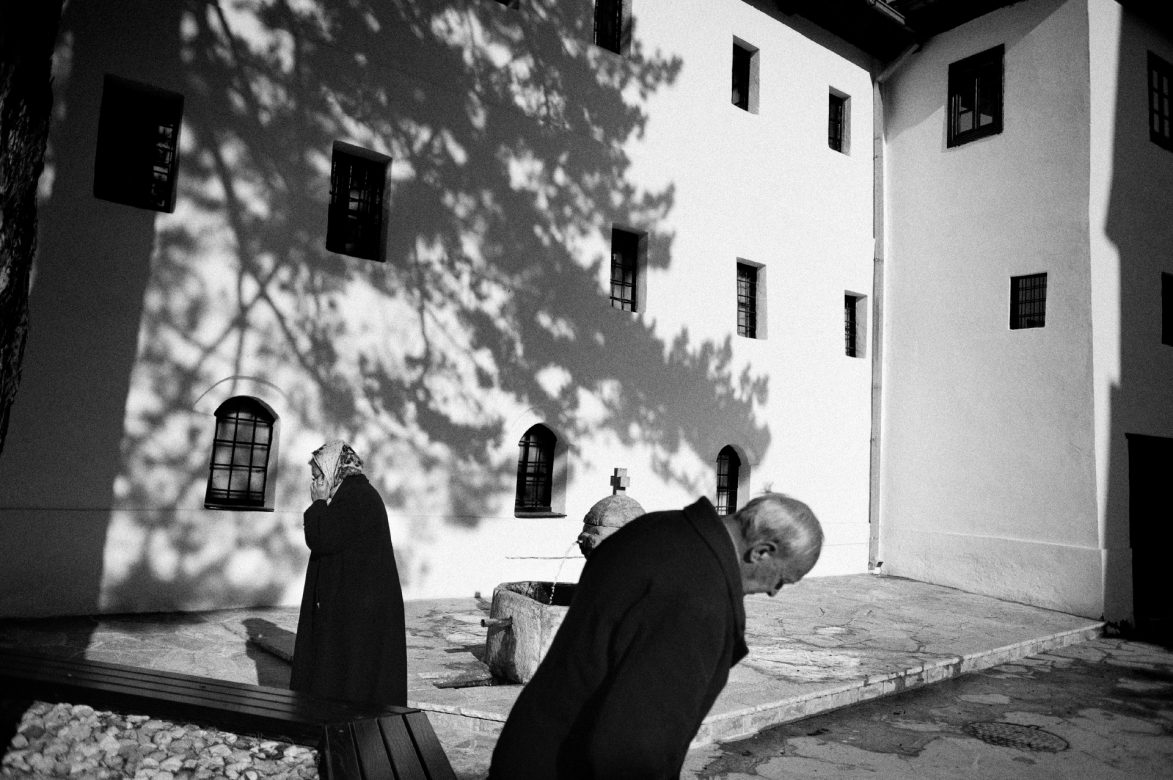

In Djakovica, 4 serbian women live in totally isolation inside the monastery of the assumption. The Serbs before the war was 3000 today they are the only 4 women Serbs in town. The conflict between ethnic Albanian majority and Serb minority is the basis of persistent political instability and social life of Kosovo. Djacovica, 2012. Kosovo.

Night landscape inside visoki Decani Monastery. Decani, 2012. Kosovo.

A cow donated by monks to Nebojša's family. In 2011, thanks to a special fundraising monks of the Visoki Dečani Monastery were able to give about 15 cows to families who needed it most. Žac 2012.

The passage of Kulina, on the border with Montenegro. In Kosovo in winter it is very difficult pass the Montenegro Border by the car. This is a problem for the monks who need to stock up on supplies in neighboring countries because they can not buy anything in Kosovo. Kulina 2012. Kosovo.

Faithful at the monastery of Visoki Dečani. The Visoki Dečani monastery was founded in 1327 by King Stephen Dečanski. Inside there is the largest medieval church in the Balkans with, inside it, the largest byzantine fresco which has been preserved to us. Since2004 it is in the list of UNESCO World Heritage Site and it is under protection of UN and Kfor. Today there are about 30 monks. Dečani, 2012. Kosovo.

The beginning of the ceremony is played with "Symandron". It's an ancient instrument, fruit of a millennium of mimicry, perfected by defeated Christians; its call to prayer is a discrete one. It does not cause any irritation to the ruling classes because here, in Kosovo, Orthodox Christians do not feel like ringing the bells. Dečani, 2012. Kosovo.

The monastery of Gracanica, which is also a UNESCO World Heritage in 2004. After the war the population was concentrated around the monastery by growing a real village, the only one with a Serb-majority population Gracanica, 2012. Kosovo.

The monastery of Visoki Decani, which is situated in the western part of Kosovo. During the Kosovo conflict of 1998-1999 the monastery brotherhood openly stood against the violence as a way of resolving the conflict. The monastery sheltered refugees of different ethnicities and distributed food parcels in the area. Decani, 2012. Kosovo.

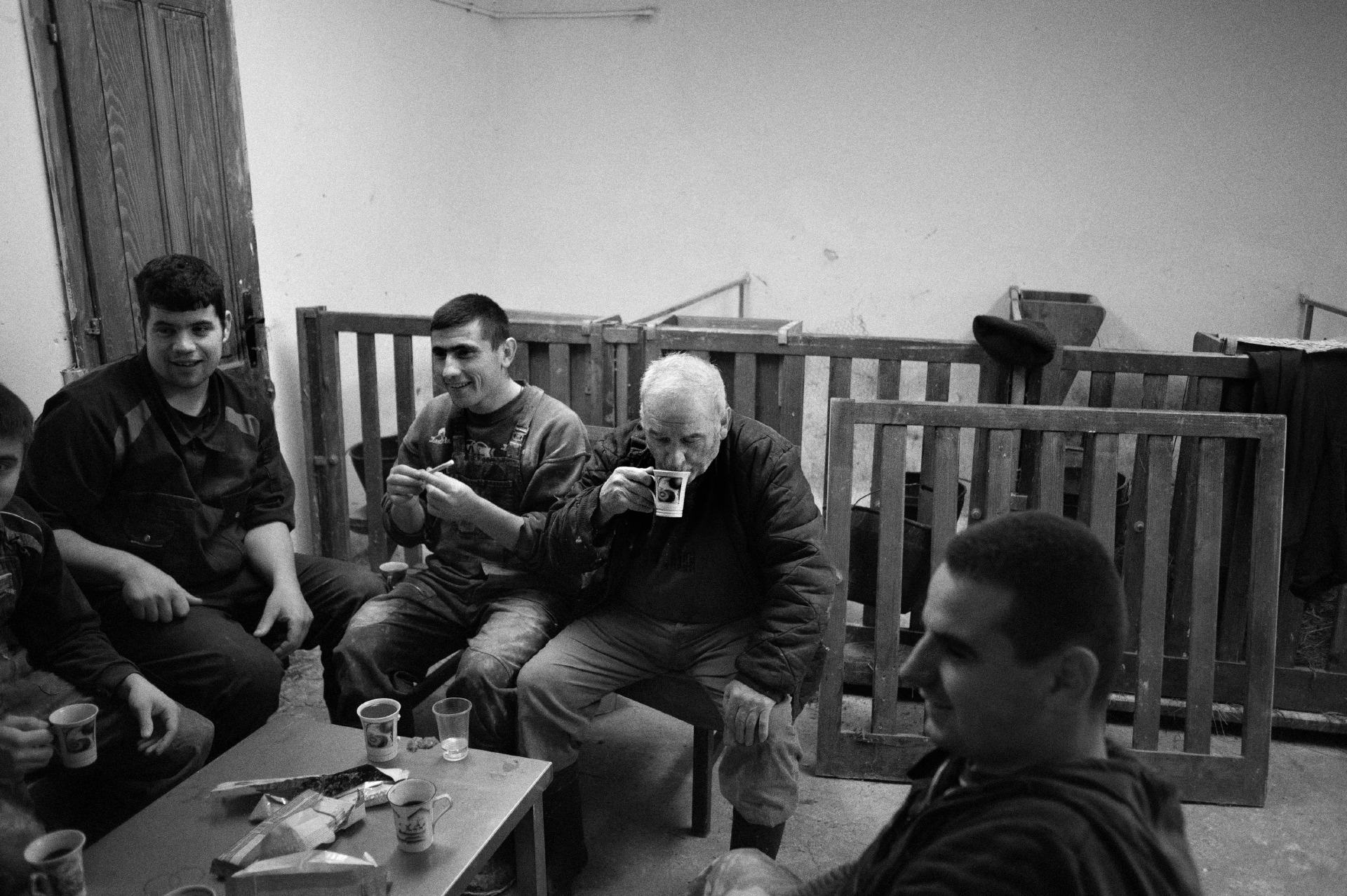

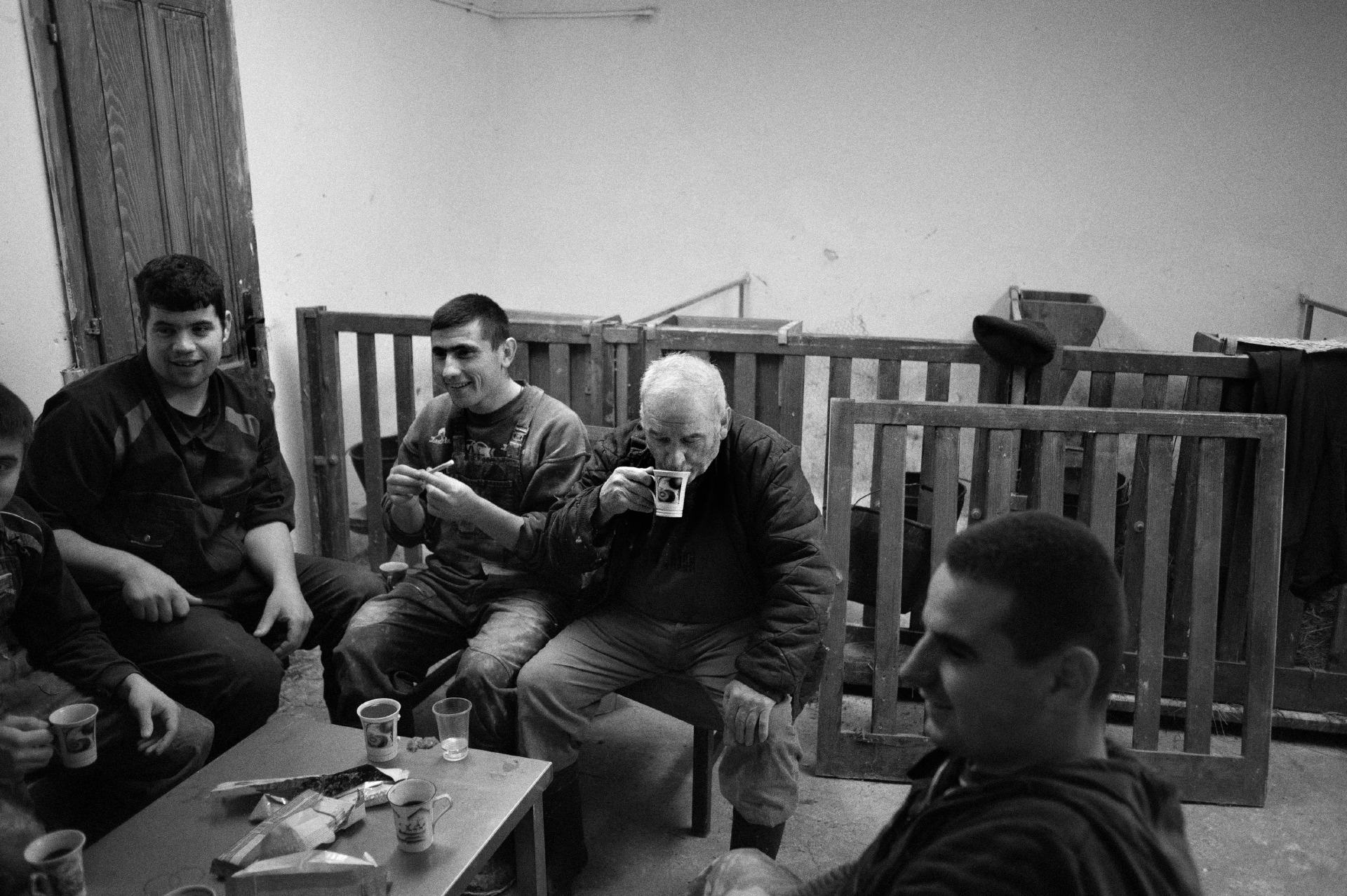

Inside Decani monastery people speak with monks about thei situation in the enclaves. In Kosovo tens of thousands of people still live in enclaves without any guarantee for human rights, without the right to work, health and education. The monks of the monastery of Decani try to give help to people who lives in the enclaves, providing them with firewood in the winter, food, clothing and so on. Decani, 2012. Kosovo.

Around the Visoki Dečani Monastery. Monks can walk freely only within the walls of the monastery and the outer fence. Dečani 2011. Kosovo.

In the Monastery of Djakovica, 4 serbian women live in totally isolation, they can not move freely only even to go out to buy food. The Monastery of Visoki Dečani has taken the responsibility of this woman. The monks escorted by KFOR and traveling with military vehicles visit them at least once a week, bringing them food, medicine, firewood and other basic needs. Djakovica 2012.

A few nights before Christmas a monk walks in the mountains to cut a round piece of oak which is turned on the Christmas night. That's an Orthodox tradition "the log of Christmas". Visoki Dečani monastery, Dečani, 2012. Kosovo.

A carver monk at the Monastery of Visoki Decani. They don't have, outside the monastery, any point to refer. Monks have to be totally self-sufficient in their daily lives: everyone of them has a specific role inside the comunity. Decani, 2012. Kosovo.

Faithful during the ceremony at the monastery of Visoki Dečani. The Visoki Dečani monastery was founded in 1327 by King Stephen Dečanski. Inside there is the largest medieval church in the Balkans with, inside it, the largest byzantine fresco which has been preserved to us. Since2004 it is in the list of UNESCO World Heritage Site and it is under protection of UN and Kfor. Today there are about 30 monks. Dečani, 2012. Kosovo.

The iconoclastic rage has always led to the disfigurement of the frescoes in the churches. Prizren, 2012. Kosovo.

The monastery of Gracanica, which is also a UNESCO World Heritage in 2004. After the war the population was concentrated around the monastery by growing a real village, the only one with a Serb-majority population Gracanica, 2012. Kosovo.

During an Orthodox baptism inside the Visoki Dečani Monastery. After the war the amount of believers who are baptized in the Kosovo Monasteries has fallen dramatically. Decani, 2012. Kosovo.

Faithful in the refectory of the Visoki Decani Monastery. Today in Kosovo, 90% of the population are Muslim albanian. Only a small percentage are serbian Orthodox. Nowdays they go to the monasteries only for the main religious services, such as Christmas and Easter, because they are scared from high risks of attack from albanians. Decani is a small town where ethnic and religious hatred is still very strong. Decani, 2012. Kosovo.

St. Cosmas and Damian's Monastry is situated in the village of Zociste near Prizren. Before war the Monastery used to be frequented by Albanian and Roma Moslems who had special respect for this shrine. Usually they would bring their sick to "sleep with saint" under the holy relics of SS Cosma and Damian. Zociste, 2012. Kosovo.

Father Milenko, pastor of Velika Hoča inside the Church of San Nicola. Velika Hoča is currently a Serb enclave, before the war lived here 1500 people, now are just over 800. The pastor is a point of reference for the whole community. Velika Hoča, 2013. Kosovo.

Inside the farm of the monastery of Visoki Dečani. Here many Serbs live and work. This farm produces food and manure for several monasteries in Kosovo. Dečani 2012.

Frescos inside Zociste Monastery. In the summer 1999, after Kfor got there, some terrorists have attacked the monastery, and set it on fire. The monks were all saved at last moment. In 2004 the monastery was rebuilt with help of Italian Army. Now live there three monks. Orehovac, 2013. Kosovo.

Faithful during the ceremony at the monastery of Visoki Dečani. The Visoki Dečani monastery was founded in 1327 by King Stephen Dečanski. Inside there is the largest medieval church in the Balkans with, inside it, the largest byzantine fresco which has been preserved to us. Since2004 it is in the list of UNESCO World Heritage Site and it is under protection of UN and Kfor. Today there are about 30 monks. Dečani, 2012. Kosovo.

Violated tombs of a cemetery near the monastery of Zociste. Many cemeteries are still being destroyed, the idea is to erase the historical memory of Serbia. Orahovac, 2013. Kosovo.

Father Luca during one of the ceremonies of Easter "The log of Christmas". Dečani, 2012. Kosovo.

Night landscape inside visoki Decani Monastery. Decani, 2012. Kosovo.

Visoki Decani Monastery, the processions of the most important rituals take place around the church but strictly inside the monastery's walls. Decani 2012. Kosovo.

One of the most important problems to the reconciliation between the two divided ethnically and religiously communities, is the humanitarian issue of missing persons. According to EULEX, there are still about 1,800 people disappeared in the conflict in Kosovo, both Albanian and Serbian. Decani, 2012. Kosovo.

Visoki Decani Monastery, the processions of the most important rituals take place around the church but strictly inside the monastery's walls. Decani 2012. Kosovo.

The Monastery has survived after the Kosovo war (1998-2000) and the Brotherhood today lives as an isolated Serbian Orthodox island among hostile Kosovo Albanian Muslim population. Dečani, 2012. Kosovo.