I’m proud to be one of the 12 finalists of the Leica Oskar Barnack, LOBA 2020, with the project “Displacement – New Town No Town“.

Giovanni Cocco condenses documentary subjects and transforms them into touching metaphors. His “Displacement: New Town No Town” series is dedicated to L’Aquila in Abruzzo, Italy, a town destroyed by an earthquake in 2009. The ruins were rapidly cleared away and temporary housing built – for the inhabitants, the only thing that remains of their old home town is the memories. Cocco does not document the devastation, but rather questions what it is that makes a town a place worth living in.

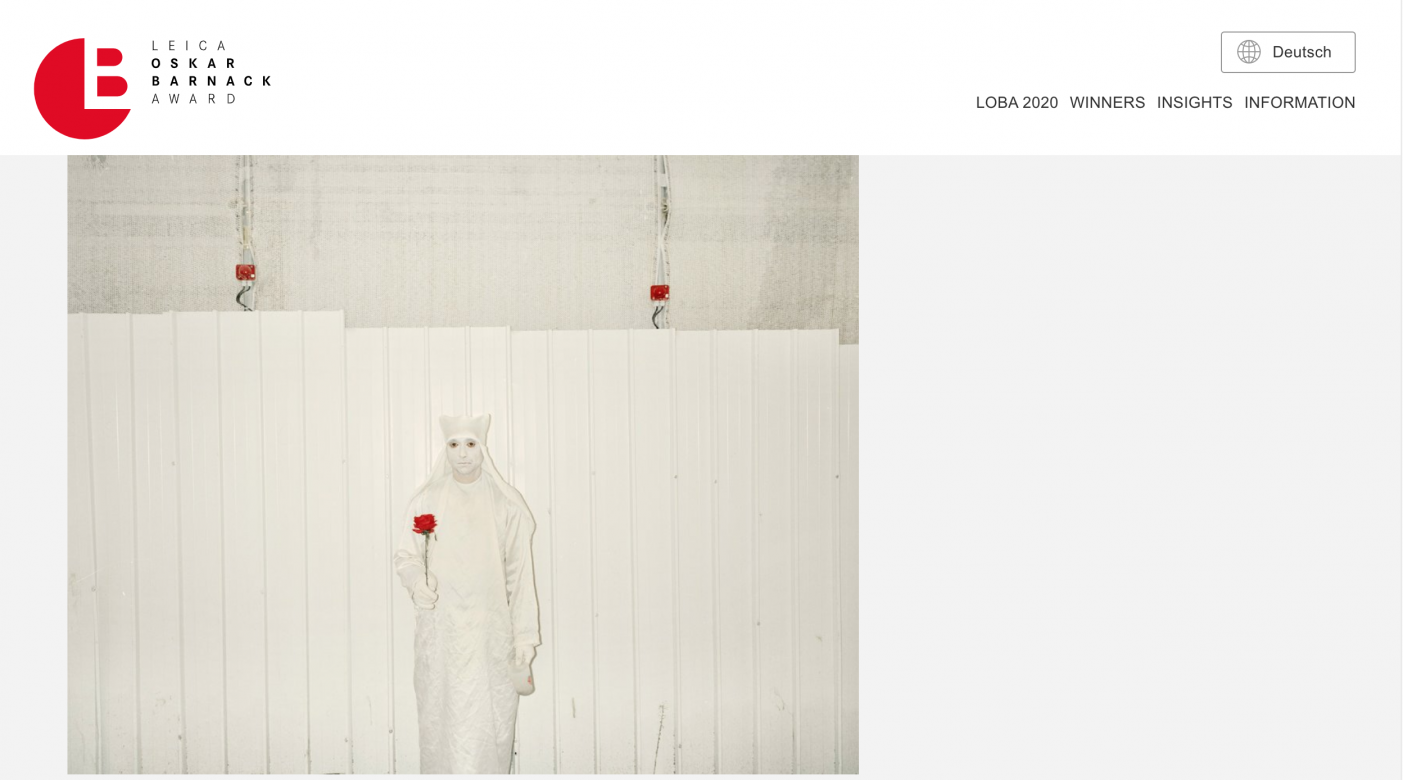

A flamingo under a plastic sheet: an exotic figure of a bird, protected and waiting patiently to return to its familiar setting. This motif is characteristic of Giovanni Cocco’s long-term project “Displacement: New Town No Town” (2012–2019). When the tectonic plates under L’Aquila shifted, on April 6, 2009, life for its 70,000 inhabitants changed irreversibly in one fell swoop. Literally speaking, no stone remained on top of another, and 308 people died. The survivors found themselves faced with the ruin of their former existence – in both the material and the intellectual sense. It was the latter aspect, in particular, that interested the photographer. “I didn’t want to show the earthquake disaster, but rather the psychological consequences of the reality that has arisen as a result.” He was concerned with the question of what an urban living environment means from a socio-cultural perspective. “What is left of a town that has lost its inhabitants? Where does the physical town end, and the living one begin? What about the genius loci?” Cocco wonders.

“I understand that I have found the right story, when my imagination starts to preview images. Then I just need to create them.”

Over the years since 2012, Cocco has observed how the Vatican has been quick to start rebuilding the churches. He saw how many houses, even full streets, have been restored; however, even though they are actually functional, the buildings have remained like empty film sets. There are no shopping streets, no theaters, and no cinemas. Barrack-like constructions intended to house many people were rapidly put up – houses, but not homes; yet, as is so often the case, temporary solutions became permanent ones. The more time passes, the more absurd the contrasts appear, as seen in the ivy-covered cars, and the auspicious reconstruction of the past, reflected in reconstructed historical buildings. “I’ve been driven by the intention to document how a city can silently witness the dissolution of its identity, while coasting for survival,” the photographer explains.

Cocco’s images reveal a sense of being lost. They are a mosaic representing the term homelessness, and of being at the mercy of politics, which often determines the fate of many. Cocco quotes from David Harvey’s book “Rebel Cities: From the Right to the City to the Urban Revolution” (2013): “In creating the city, man has recreated himself.” Then, Cocco goes on to say, “Observing what is happening in L’Aquila is seeking to observe what is happening today, concerning the peoples Right to the City.” In this sense, L’Aquila became a metaphor for Cocco: what you find there, in condensed form and in fast motion, is the same thing that can be observed in other cities. Does the idea – in the sense of the turbo-capitalist maxim defining the new, instead of the old, as a manifesto for a successful future – always work? A little hope does still shine through, though – if only the sheet of plastic was not in the way.

The Leica Oskar Barnack team